Chilli (Capsicum spp)

About Chilli

Chilli, botanically classified in the genus Capsicum, is the fruit responsible for the world’s love affair with heat. From tiny, explosively spicy peppers to plump, juicy sweet varieties, chillies offer a mosaic of flavors: floral, smoky, fruity, grassy, or fiercely hot. Their signature burn comes from capsaicin, a unique compound that exhilarates the palate and inspires culinary creativity worldwide.

Chilli is used fresh, dried, powdered, smoked, fermented, stuffed, or even candied. Its ability to transform dishes—adding depth, brightness, and addictive fire—makes it indispensable in Mexican salsas, Indian curries, Sichuan stir-fries, North African harissa, and countless other global cuisines.

The History of Chilli

Chillies are native to Central and South America, with archaeological evidence of cultivation dating back over 6,000 years in Mexico and Peru. They were central to ancient diets and rituals among the Aztec, Maya, and other civilizations, cherished as much for heat as for their medicinal and preservative powers. With the Columbian Exchange in the 15th and 16th centuries, Portuguese and Spanish traders carried chillies across Africa, Asia, and Europe, where they ignited culinary revolutions—transforming everything from Indian vindaloo and Thai som tam to Hungarian paprika and Korean gochujang. Chillies quickly adapted to local climates, birthing an astonishing diversity of shapes, colors, and heat levels.

The Science of Chilli

Chillies owe their burn to capsaicinoids, primarily capsaicin, which binds to pain receptors and tricks the body into feeling heat. The heat is measured in Scoville Heat Units (SHU), with varieties ranging from mild bell peppers to searing Carolina Reapers. Chillies are rich in vitamin C, provitamin A, potassium, and antioxidants like flavonoids and carotenoids. Capsaicin’s health benefits are widely studied, including potential roles in boosting metabolism, reducing inflammation, and even contributing to pain relief. Interestingly, the pungency serves as a natural deterrent against mammals but doesn’t affect birds, enabling effective seed dispersal.

The Geography of Chilli

While chillies originated in the Americas, they now thrive in warm climates around the globe. India, China, Mexico, Turkey, Nigeria, and Thailand are major producers, each favoring different species and cultivars suited to their regions. Local soil, rain, and sun affect everything from heat and aroma to the vibrancy of color. In Mexico’s Oaxaca, native landraces abound; in Hungary’s Szeged, sweet paprika reigns; in Sichuan, China, local chillies are bright, oily, and aromatic; while in Southern India, Guntur chillies are prized for their punch.

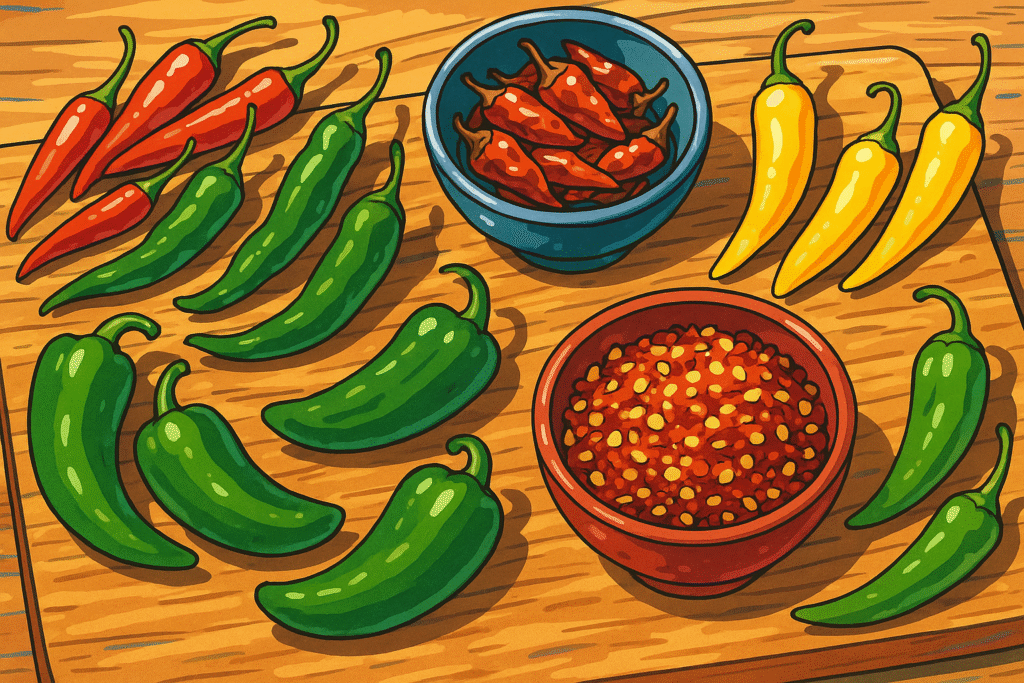

Varieties of Chilli

Bird’s Eye Chilli (Capsicum frutescens)

Tiny but devilishly hot, these are essential to Southeast Asian cuisines, lending heat and brightness to Thai stir-fries, sambals, and dipping sauces.

Jalapeño (Capsicum annuum)

Well-known for medium spice and fresh, grassy flavor. Popular in Mexican cuisine, stuffed as chiles rellenos or sliced into salsa and nachos.

Kashmiri Chilli

Iconic in Indian cuisine, this chilli is moderately hot but famous for its vivid red color and mild smokiness—ideal for curries, tandoori marinades, and chutneys.

Padrón Pepper (Capsicum annuum)

Native to Spain, these small, green peppers are mostly mild but with occasional fiery surprises. Served blistered with salt as a classic Galician tapa.

Bhut Jolokia (Ghost Pepper, Capsicum chinense)

Once ranked the world’s hottest, this North-Indian chilli is intensely pungent, fruity, and smoky. Used cautiously in pickles, chutneys, and ultra-hot sauces.

Aji Amarillo (Capsicum baccatum)

Peruvian staple with medium heat and sunny, fruity flavor—key to ceviche and traditional causa.

FAQs All your questions about Chilli: answered

Why do chillies taste hot?

Capsaicin binds with receptors on your tongue that usually detect heat, triggering a burning sensation. This is a form of chemical “trickery,” not actual heat.

How do you reduce chilli heat in food?

Remove seeds and inner membranes, where capsaicin concentrates. Dairy (like yogurt or milk), sugar, or acidic ingredients help temper the burn in sauces and stews.

Are chillies good for your health?

Chillies are packed with vitamin C, carotenoids, and minerals. Capsaicin may aid metabolism, ease pain, improve circulation, and even act as an antimicrobial—but excessive intake can irritate sensitive stomachs.

Why do some chillies taste fruity or smoky, not just hot?

Chilli varieties contain unique blends of volatile aromatic compounds, giving each type distinct notes (citrus, berry, chocolate, smoke) that shine when dried, roasted, or fermented.

How are chillies used differently around the world?

Raw and fiery in Mexican salsas, smoky and rich as paprika in Hungary, fermented in Korean gochujang, ground for North African harissa, or pickled in Mediterranean mezze—chillies adapt to every regional palate and tradition.